One month ago, a bit of musical whimsy staged a century ago was extracted and extrapolated upon a set of circumstances, which, in turn, fostered an outpouring of comment and diatribes. This should be a cause for surprise and it certainly was worrying in that this needless controversy illustrates a fragmented Lankan community and underscores the already existing lines of societal fracture.

The Tower Hall, Maradana – after its restoration and refurbishment in the 1980s

The Tower Hall, Maradana – after its restoration and refurbishment in the 1980s

On reflection over these recent eruptions of public distaste, poor taste and sullied decorum, one feels a sober analysis is apt. Discussing merits and demerits is outside of my province, but understanding the flow of the tide (and of what is revealed in the times past) would help. There may well be vultures that prey on culture, but that should hardly interest a nation of sentient beings whose real interest, as always, is about getting on and going on.The simple trigger happened to be a song that has the accepted title, "Dunno Budunge". Context is EVERYTHING in connection with this song! As it stands, the title makes no sense at all. It forms an incomplete thought within Sinhala syntactical norms. These two words are the first in the opening line of verse of the first stanza of the lyric of a song that, by rights, should bear the title "Anurādha Nagaraya". The subject and content in the lyric is just an idealized evocation of the idyllic grandeur of the capital city o f Anuradhapura; and the song (yes, a mere song, not an oratorio, an incantation nor a profound sacred pronouncement nor extract from a philosophical treatise) was included in the stage play "Siri Sangabo", popular in the first years of the 20th century (c. 1903) after its being staged at the Public Hall in Colombo.[i]

The paean starts with these two words, and continues "Dunno Budunge sri dharma skundha." [literally: "Those that possess knowledge (dunno) of the weight and value (skundha=Mass/weight) of the Buddha's teaching ….."]. Beyond these words, the remainder of the song refers not to the Teaching, nor the person of the Teacher, nor alludes to any aspect of the acts of devotion; but it does reveal a 'pious' sentiment as generated by seeing the beauteous aspect of the ancient capital city (kingdom) of Anuradhapura, which at the time the play was staged lay in ruins and almost completely submerged under the jungle tide, save for the initial restorations affected by the Department of Archaeology established by writ of Her Majesty's Government under Queen Victoria. The setting for the play is what takes matters back to the grandeur lost, when Lanka's (Sinhala) kings ruled from the north central province.

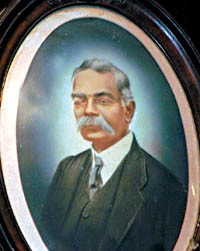

The dramatist was John de Silva (who was both a teacher at Wesley College and also a proctor of the Supreme Court) who composed the lyric. His collaborator in the work was an Indian, Vishwanath Lawjee from Bombay.

John de Silva, as always, dapper in his 'Western' (!?) three -piece suit and tie, who, with all his affinity with the Sinhala renaissance, never sought to follow the lead of his cohort in adopting a 'national' dress or costume)

John de Silva, as always, dapper in his 'Western' (!?) three -piece suit and tie, who, with all his affinity with the Sinhala renaissance, never sought to follow the lead of his cohort in adopting a 'national' dress or costume)

In his monumental thesis "The Folk Drama of Ceylon"[ii] Professor Ediriweera Sarathchandra discusses in his eighth chapter the emergence of the "nurthya" [also written as nruthya] style, emanating from the earlier nādagam theatrical oeuvre, and, also mentions John de Silva's disquiet as regards that earlier established tradition. De Silva wished to usher change. Ediriweera's text dwells on the influences prevalent at the time and of the Parsee, Baliwallah Theatrical Company who set up the Elphinstone Dramatic Company of Bombay, and later also established a place in Maradana in Colombo. In the 1880s[iii] Balliwallah's troupe performed in Colombo. Ediriweera says, "Balliwallah is said to have performed for over three months to packed audiences in the Floral Hall, a wooden structure in the old Raquet Court in the Pettah".[iv] He then quotes from The Ceylon Observer, July 9, 1944, and refers to an article reviewing the trends of that time in the previous century .

The writer of that Observer review, Wilmot Wijetunge, is referred to as being "intelligent and knowledgeable", and is quoted verbatim: "Gorgeous and scintillating costumes, colourful and artistic sceneries before brilliant kerosene-oil footlights, breathtaking spectacular mechanical devices (of marble palaces floating up into thin air, and of wondrous magic treasure caves), rapid dramatic sequences grasped in spite of a foreign language and, above all, the haunting airs of the music of North India –all these fascinated and captivated the onlooker accustomed to the slow- moving, bald, and unsophisticated Nadagama. Henceforth it was destined to yield precedence to this new dramatic form born in such fortuitous circumstances –to the Nurtiya (sic)."[v]

Nruthya then, was the 'new' theatrical experience and was popularized within the crowded space of The Tower Hall, Maradana. It was in this locale that John de Silva exerted his considerable influence, indeed, as did several others of his ilk.

De Silva's "Siri Sangabo" was repeatedly performed at this venue after its premiere in 1903. The drama was composed, created and staged in a milieu that is described by Sarathchandra thus: "[de Silva's] aim was to rescue the Nurtiya from the position it had descended to, as the vehicle of a hybrid Anglo-Oriental culture, and to make it a medium for the propagation of national and religious sentiments among the people. He drew this themes, therefore, largely from episodes in Sinhalese history and legend, and with the help of these he tried to recreate something of the splendour of the past, and to set before the people the example of kings like Siri Sangabo and Dutugamunu, and thereby evoke emotions of piety and of respect for the ideals of our forefathers."[vi]

Commenting on the prevalent styles of musical-theatre in Lanka in the immediate post-Balliwallah period, Sarathchandra writes: "The songs that follow (the introductory interventions of a narrator-jester) have tunes drawn from a variety of sources, Hindustani, Tamil and even English. In the text of the play, the first line of an existing song is given at the beginning of each song, to indicate the tune to which it is to be sung, and, it is interesting to note that one song has to be sung to the tune of "Jack and Jill went up the Hill". This custom of prefixing the first line of an existing song to indicate the tune began with the adoption of Hindustani airs, and continued up to the time of John de Silva…".[vii]

Siri Sangabo

The story line of this musical-play refers to a fantastic account of a 'saintly king' of that name, who lived and reigned amidst much palace intrigue in the early centuries of the Common Era, and who is reported to have decapitated himself and handed over his severed head to his humble benefactor, in order that such a grisly 'sacrifice' would accrue monetary benefit to this impoverished subjects in his Kingdom at Anuradhapura. The claimed 'nobility' of this self-destructive act is held up as an ideal worthy of imitation. Attanagalla in the Anuradhapura district, is a monument to this king. [Ref: Mahawamsa 58-97].

Now, more than a century after the play's composition, a London based, Lankan born singer was the subject of a rallying call for a figurative artistic decapitation to be pronounced upon her. Her name is Kishani Jayasinghe. She had been a Senior Prefect in a well-known school, Visakha Vidyalaya in Colombo and had decided to pursue a career employing her considerable gifts as an actress and singer. Today, after much training and the acquisition of skills at the highest levels before her debut in the UK, Kishani has been warmly accepted in the verity of the world of European classical Opera. Her reputation has been discussed elsewhere.

Kishani Jayasinghe, however, was recently reviled in public and 'convicted' of singing the song "Anuradha Nagaraya" (a.k.a. "Dunno Budunge") in a vocal rendition that was considered inappropriate and destructive of the values that that particular song is said to be imbued with. The Internet social media was alive with the hubbub of jeering and insults against her bel canto interpretation of this century old staple of the Tower Hall theatre era.

Kishani is certainly not the first person to deliver the lyric of this same song in the Italian bel canto style. In the 1920s and 1930s another versatile singer was the tenor Hubert Rajapakse. His world straddled both the 'western' and the 'oriental', although his performances in public were usually modeled on the bel canto, and included lyrics in English, Italian and also in his native tongue, Sinhala. Rajapakse has even an acetate record of his rendition, and there are likely a handful of persons in Colombo who may have access to that rare gem. Curiously, Rajapakse has either erroneously or deliberately pronounced the opening two words as "Dharma Budunge", which, of course, does not make much sense. The rest of his rendition is of the lyric as they were written. His transcriber may well have to take the blame for the error!

It is by pure chance that I am acquainted with Hubert Rajapakse's work. That is because my father's youngest sibling was a trained tenor in the bel cantotradition, and his first voice teacher was Rajapakse.

Quite apart from this singer, there were many others who have also been heard in performance singing the same song and the same lyric, obeying the same tempi and identical intonation as associated with the classical Italian style. None of them, perhaps, sang it thus at an open-air event, before a wide audience at such a venue and extended via the electronic media, to include even larger numbers than were gathered at the celebratory event on February 4th, 2016 on Galle Face in Colombo. It was Kishani who had to suffer the consequence.

However, murmurs against 'tampering' with this perennial actually were heard in 2013, when the Symphony Orchestra was in public performance during the CHOGM 2013 celebrations in Colombo. HRH Prince Charles was in attendance along with heads-of-state of the Commonwealth and they were treated to a concert. A close friend of mine, and erstwhile conductor of the of the Symphony Orchestra, and former principle French Horn player in the same orchestra, was commissioned to arrange for this concert an orchestral version of "Anurādha Nagaraya" (Dunno Budunge).

The CHOGM concert was conducted by the guest from London, maestro Gregory Rose. Conductor Rose rendered justice to the score, which was projected in the lush imaginatively arranged style of a full instrumental version, akin to an interlude as may have been composed by, say, a Ralph Vaughn Williams. The audience obviously relished the concert performance. For some it meant nothing. For the few from Lanka who may have graced the concert, it was an interesting interpretation with breadth and scope hitherto unheard in a rendition that was purely instrumental, with no voice. On the other hand, there were a few, including some players, who chose to attack the arranger of the score, and condemned him viciously for having 'baptized Dunno Budunge'!!! A rather telling employment of phrase, this – a criticism which indicates the displeasure of the detractors who considered that a piece that was a 'nationalist' vehicle of 'religious' significance was now coopted in a different � ��mould' alien to its culture.

This unexpected response set off an informal, albeit feverish, bit of research by a friend of the commissioned arranger of the piece. This inquiry into the origins of the tune was initiated by Udaya Siriwardhana (son of the late, revered Principal of Visakha Vidyalaya, Colombo, Mrs. Eileen Siriwardhana, and of the doyen among the civil servants of yesteryear, the late Mr. D.B.I.P.S. Siriwardhana).

European Elements

As noted above, John de Silva's collaborator was the Indian Vishwanath Lawjee, and he was chosen because de Silva wished to bring in a varied ethos into his work, given his disenchantment with the prevailing custom. As Sarathchandra notes: "he eschewed Nadagam tunes completely and attempted to make Nurtiya music more systematic…..[In earlier examples] The tunes were more or less haphazardly chosen, and, if at all, only in accordance with lay notions of their suitability for the various situations in the story. John de Silva decided to apply the Sanskrit theory of rasa or dramatic sentiment to his plays."[viii] However, as we have also established above, there is the insight offered us into the practice of employing introductory bits of other established tunes from different sources, and incorporating them in the body of the melodic content of the plays of John de Silva and his cohort. Lawjee, notably, came from Bombay, and was acquainted with a variety of sophisticat ed musical traditions, including the northern Indian traditions and formal arrangements of melody and rhythm.

Was the borrowed bit of the melody for Dunno Budunge from such an extraneous source? This was an interesting question, and Udaya Siriwardhana chose to chase after the available evidence.

In the 1820s a former member of Ceylon's Judiciary, one Johnston, was now holding a senior position in the Colonial Office in London. In 1829, in connection with what is deemed to be an edict for "the abolition of slavery" [not to be confused with such attempts later in the United States of America], there was to be an event in Ceylon for which it was decided to do something original.

Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Alexander Johnston: 1775-1845 … https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Johnston_%281775%E2%80%931849%29

Alexander Johnston: 1775-1845 … https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Johnston_%281775%E2%80%931849%29

Johnston was on good terms with Felix Mendelssohn the composer. Mendelssohn was equally at home in England as he was in Leipzig, and was known to be a very winsome conversationalist, fluent in English as much as in his own language. Since such camaraderie existed between them, Johnston had, in a 'by the way' fashion, asked if Mendlessohn would write a work. As Udaya and his contacts have found, this is borne out by the records at the Mendelssohn archives and entries in the composer's diary as well as in a letter or two. There is a record of the letter of thanks from Johnston, saying that the piece was good and was well received at its performance. This was an orchestral piece, it may be noted. Sadly, even though published, not a scrap exists of that orchestral work!!!! The Mendelssohn archivists admit to that lack.

However, following the 'popularity' of the piece for Ceylon, Mendelssohn had later written a shorter work for solo piano. That was not a reproduction of the whole orchestral in a fresh setting. Rather, it was a completely new piece, but it is surmised that he did employ thematic elements from the earlier composition. Those thematic elements were identical with the tune that was used by Lawjee and John de Silva as a vehicle for his paean. In the turn of the century period, at the end of the 19th, that tune had currency and acceptance.

John de Silva and Lawjee's work does not pretend to be anything outside the mould of the European structure of musical theme and development, using a minor mode and then modulating into a major theme for the more 'valorous' subsections of the song. This kind of stylized or formalised musical structure was and is completely alien in the South Asian traditions in musical composition of any sort.

When Rev. W. S. Senior of Trinity College Kandy composed the English "Hymn for Ceylon", his collaborator in Ceylon was none other than Devar Suriya Sena. In the early 1950s (and not long since the Independence of Ceylon from British governance), Suriya Sena borrowed the tune associated with de Silva and Lawjee, save for the opening mode being a major scale rather than the minor mode as employed by Lawjee. There does not appear to be any 'murmurs' against that adoption and adaptation in the literature available on this topic …. until now.

It is yet to be indubitably established that Dunno Budunge aka Anurādha Nagaraya was, in fact, extracted from Mendelssohn's composition for piano. Scholars are even now working to determine this. The Mendelssohn Archives in Europe are also keen to trace these links, since the correspondence does allude to the composer obliging a friend in the Colonial HQ in Victorian London.

Therefore, … Dunno Budunge has had a mixed musical provenance, but primarily it is a song of the Lankan stage, no more, no less. It could be measured as being on par with the works of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice.

************** Arun Dias Bandaranaike has been a professional broadcaster, newscaster, commentator and moderator for around 25 years, serving with the national broadcast services in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, and Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation.

ALSO SEE ... Arun Dias Bandaranaike: "Shooting down a Star,"4 March 2016, https://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2016/03/03/shooting-down-a-star/#more-20021

Kamanthi Wickremasinghe: "Dilemma over 'Danno Budunge'," Daily Mirror, 23 February 2016, http://www.dailymirror.lk/105838/Dilemma-over-Danno-Budunge-

FOOTNOTES

[i] Published by The Dept. of Cultural Affairs, Ceylon- 2nd Ed. April 1966.

ii The Folk Drama of Ceylon- Sarathchandra. p.130.

iii Ibid pp. 130,131

[iv] Ibid p.131.

[v] Ibid p.131.

[vi] Ibid p.133

[vii] Ibid p.131

[viii] Ibid p.134

About these ads

Like Loading…Related

Julie Bishop canes WeissIn "accountability"

Marga and CHA provide a Third Narrative of Eelam War IVIn "accountability"

Views of British Ceylon and LankaIn "cultural transmission"

1 Comment

Filed under British colonialism, Buddhism, cultural transmission, education, heritage, historical interpretation, Indian traditions, landscape wondrous, life stories, nationalism, performance, plural society, politIcal discourse, sri lankan society, unusual people, world events & processes

← Mount Lavinia Hotel celebrates its 210th Year with A Literary Feast

Shooting down a Star →

One response to "The Evocative Minor Chords of 'Dunno Budunge' and the Current Discord"Source: The Evocative Minor Chords of 'Dunno Budunge' and the Current Discord

No comments:

Post a Comment